The Irish Palatines were early pioneers in Canada, originally settling primarily in Ontario and Quebec, and then branching out to western Canada. They are known for having brought Methodism to the New World. Their origins go back to the Rhineland Palatinate and other Germanic principalities of the Holy Roman Empire which saw a mass migration to England in 1709.

Conditions in these German lands had been unsettled at least since the time of the Thirty Years’ War which ended in 1648. Subsequently, the area was constantly being invaded and plundered by Louis XIV of France who wanted to annex the territory. The people in this area were heavily taxed to pay for the wars and the opulent lifestyles of their princes. They were poor husbandmen and vinedressers who worked in the vineyards, and when a severe winter hit Europe in 1708–1709, their crops froze and their economic circumstances plummeted even further. Early in 1709, their hopes for a better life were raised when a “Golden Book” began circulating amongst the population, bearing a picture of England’s Queen Anne on the cover and promising a prosperous and easy life in America. The proprietors of England’s American colonies had been pushing for the naturalization of foreign Protestants as a way to encourage people to settle in their lands without depleting the population of England, and in March of 1709, Queen Anne passed a naturalization act that was favourable to foreign Protestants.

With the prospect of a better life in view, hordes of Palatines and others from the southwestern German principalities—mostly Protestants of the Lutheran and Reformed churches—started moving up the Rhine that spring. They travelled to Holland and boarded boats for England, expecting to be given free passage to America. By late summer, about 10,000 Palatines had arrived in London, where they were housed in tents as refugees.

Queen Anne did not intend to settle them in America for free; that was mere propaganda. Nevertheless, about a third of them were taken to New York province where their descendants still live in the Hudson and Mohawk River Valleys. Another third were scattered in parts of England and the Caribbean and quickly assimilated. The remaining third were taken to Ireland and settled on the estates of Protestant landlords in order to strengthen the cause of Protestantism in the south. The largest group of 105 families was settled in County Limerick near the town of Rathkeale on the estate of Sir Thomas Southwell in the townlands of Court Matrix, Killeheen and Ballingrane. A smaller group of about thirty families was settled in County Wexford on Abel Ram’s estates in Old Ross and Gorey.

The Palatines were given good land at very cheap rent. Their communities were culturally distinct and tight-knit, retaining much of their German character for several generations.

The Englishman and founder of Methodism, John Wesley, visited Ireland twenty-one times, and was particularly attracted to the Irish Palatines. They, in turn, were attracted to his message of personal piety, and many became eager adherents of Methodism. Two of these converts were cousins Philip Embury and Barbara Heck. They were part of an early group of Palatines who left County Limerick and arrived in New York City in 1760. A few years after arriving there, Embury and Heck established the first Methodist congregation in America and set about building a chapel. The John Street United Methodist Church still stands in Lower Manhattan today, the descendant of that original chapel.

In 1770, the group in New York City left the urban hustle and bustle to take up new homes in the Camden Valley, northwest of Albany near the New York/Vermont border. There they built homes and lived comfortably, expecting this to be their final resting place. But a few years later, the Revolutionary War broke out, and the Irish Palatines, for the most part, supported the British. Many of the Irish Palatine men joined Loyalist regiments and fought at the Battle of Bennington and were with General Burgoyne at Saratoga when he surrendered in October 1777.

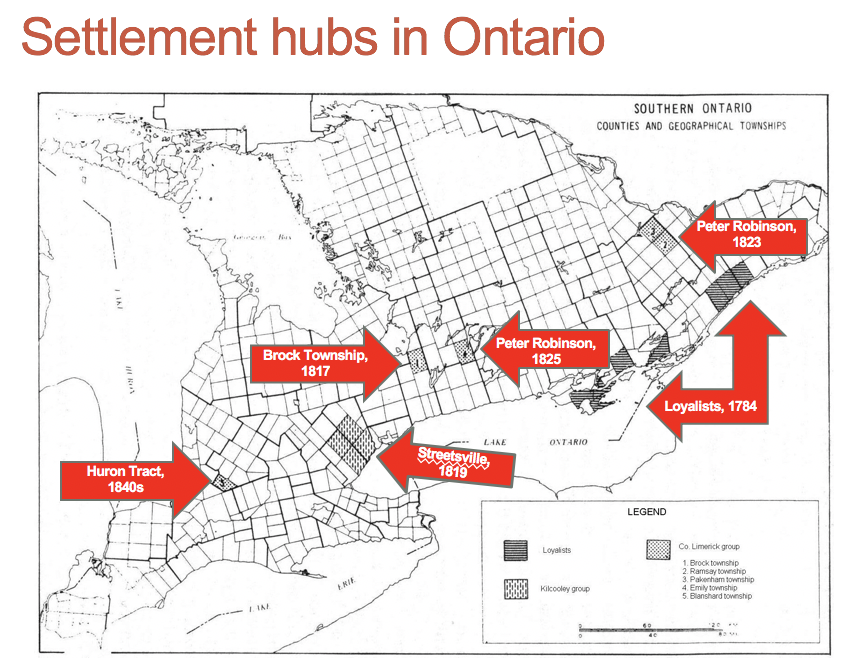

After Saratoga and Burgoyne’s stunning defeat, most of the families were forced to leave their valley homes and move to the safety of Quebec for the duration of the War. When the war was over most of the Irish Palatine Loyalists were given land in Upper Canada (present-day Ontario). A very few settled in Lower Canada (present-day Quebec). Once again, the Irish Palatines took the lead in forming Methodist classes and establishing Methodist congregations and chapels.

In the nineteenth century, the Irish Palatines who had remained in Ireland, started immigrating to Canada as part of the wave of Irish immigration to North America. The flood-gates opened in 1815 at the end of the Napoleonic Wars when Canada decided it wanted loyal British subjects, not American settlers. A few Irish Palatines made the ocean trek to Canada in the 1810s and established hubs of settlement to which other Irish Palatines were attracted. But it was the 1820s that saw widespread fervor to leave County Limerick due to economic depression, increasing rents, and a wave of sectarian violence that affected the southwestern counties of Ireland.

Most emigrated in family groups and, given the extent of intermarriage among the Irish Palatines, their kin networks were tightly interwoven. A few of them put down roots in the province of Quebec: some who were tradesmen set up shop in Quebec City; one early group sailed in 1822 and took up land south of Montreal around Napierville and Lacolle.

However, the bulk of the Irish Palatines set their sights on Ontario from the outset. They established themselves in a few locations to begin with, but by the end of the nineteenth century, they could be found in almost every township. In Canada, and especially in Ontario, the Irish Palatines found a most hospitable environment. Unlike their experience in Ireland where they formed part of a cultural and religious minority, in Ontario they were part of the majority: they were Protestant, just like two-thirds of the Irish immigrants and most of the English and Scottish immigrants as well. They were a rural people and farmed successfully or ran small business enterprises, and they were familiar with the parliamentary political system. Like the Loyalists before them, those who immigrated to Canada considered themselves loyal British subjects.

Carolyn Heald, IP-SIG Director